|

Bud Grossmann's

Words of the Week

Week of May 29, 2005

Published as Family History,

in a WIP dated May 8, 2001

© 2001 by Bud Grossmann.

All Rights Reserved.

|

|

|

|

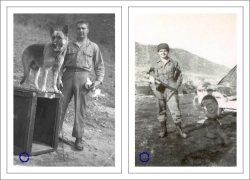

Uncle Bob in Korea, Circa 1950

Photographer Unidentified

© 2005 by Bud Grossmann

|

SHOOTING PHOTOGRAPHS

My Aunt Peg died childless. Margurite "Peg" Cummings was the widow of Grandma Grossmann's brother Eugene. When Peg passed away, about twenty years ago, her sister Aileen went through the papers and pictures Gene and Peg had left behind. Knowing I'd been fond of my uncle and my aunt, Aileen sent me some family photos that she found. When those prints—many dozens of them, but few with dates or captions—arrived in my mail, I sorted them into stacks for the families of Doris, Gordon, Robert, and Darlene. Gordon is my father; the others are his siblings. I ended up with another stack, too, a somewhat larger one, which I marked "Unidentified."

Instead of sending out the pictures, I packed them away in a box. This past January, my parents came here for a visit, and I hauled out that box and asked Dad if he would name some names.

Several of the photos, Dad told me, were of Grandma's brother Roy, who is now long gone like Eugene. Roy's wife Mary, however, is still around. My father told me Aunt Mary lives in Oregon, remarried now, to a good man named Bill Swank. Dad had their address, and I looked up their listed phone.

When I called, Aunt Mary said, Oh, yes, sure, she'd be pleased to see the pictures. And, No, she said, I needn't worry: Uncle Bill would not object to my sending photos of Uncle Roy. I mailed them, and, as weeks went by, I forgot about them.

Three or four months went by, and then Aunt Mary wrote to me. She sent a lovely letter of news and reminiscences, and she enclosed five photos, not the ones I'd sent. Two of the pictures are in color, of Aunt Mary, Uncle Bill, and magnificent salmon—Chinooks hooked in Tillamook.

Another print, black-and-white, shows Uncle Roy on an overcast day, alone beside a mown field of hay. He's wearing an Army uniform of the Second World War; the Eisenhower jacket is bunched at the belly, but the soldier's trousers are tidily tucked into the tops of his boots. Roy's hands are relaxed at his sides. His left hand holds his service cap; his right holds a hand-rolled cigarette.

The last two photos, also black-and-white and of a soldier in uniform, are ones I may have seen before. They were taken, I believe, in Korea, and they show my dad's younger brother, my Uncle Bob. In one snapshot, Bob is beside a wooden crate, a dog kennel, on sloping land with gravelly sand. On top of the kennel a handsome German shepherd stands, secured to his box by a length of light-link chain. Uncle Bob is without a hat and without a weapon; his long-sleeved, large-pocket shirt is wrinkled. He solemnly stares into the lens of the camera. In the other photo, however, Uncle Bob's expression is different. He is smiling pleasantly and standing comfortably in mud beside a topless Jeep. A thick-treaded tire is mirrored, but not mired, in a puddle. Bob is wearing a winter hat with the earflaps and bill in the up-raised position; his field jacket bulges with gear. Straps of a pack or a shoulder-holstered side arm can be seen. Bob's left hand is in his pocket, as if he is jingling change. But his right hand grips the wooden stock of a submachine gun, with a ventilated barrel and a drum-type magazine.

By the time I got to know my Uncle Bob, he was a civilian, a school teacher, a big guy, bulkier by far than the boy in these photos from the Korean War. He was quiet, with a soft and nervous chuckle. He smoked Raleighs; he lit them with a Ronson lighter. Uncle Bob told stories of hunting, fishing, or automobiles, but what he didn't say much about, at least not to me, were his duties as a draftee. He'd been wounded, that much I'd been told, but I heard it from Grandpa, not from Uncle Bob. Where, how, and how bad, I don't recall if Grandpa specified. I can ask my cousins or my dad. But Grandpa is gone, and I can't ask Uncle Bob, either, because he died in 1977 at the age of forty-eight, of a heart attack, in a bunk in a camper truck, on a summer night following a good day of fishing.

My grandfather spoke often and affectionately of his son Bob. I remember one morning when Grandpa was winding a wristwatch while waiting at the breakfast table for Grandma to put a plate of eggs and toast in front of him. This was ten years after the truce between the two Koreas. "Robert took this watch off a dead Chinaman," Grandpa declared. "Swam to the bottom of a river for it. Dried it out, brought it home, and he give it to me to wear. And by golly, let me tell you, it keeps perfect time!"

I remember my grandfather; I can't say I clearly remember his watch. But if that timepiece came to Grandpa the way he said, it would have been wrestled from the wrist of a man who had uncles and aunties, and photos and fond memories, a man with a gramp and a granny, a man with a mother, a man whose weighty weaponry at last anchored him to the rocky bottom of a clearwater stream. Somewhere, I suspect, is a snapshot of that same soldier smiling, his left hand in his pocket, as if he is jingling change. His watch cannot be seen, but it is, in that moment and eternally, I am certain, maintaining perfect time.

♦

|